The Connections Between Positive Psychology & Mental Health

In the past, many therapists focused primarily on challenges and symptoms of mental health disorders – how to treat “problems.”

In the past, many therapists focused primarily on challenges and symptoms of mental health disorders – how to treat “problems.”

The focus of mental health counseling was less on individual factors like motivation, positive thinking, happiness, and emotional resilience, and more on the manifested symptoms of mental illness.

George Vaillant (2009), a pioneer in the field of positive psychology, pointed out that old research articles on psychiatry and mental health have a myriad of discussions on anxiety, depression, stress, anger, and fear, but very little about affection, compassion, or forgiveness.

With the advent of positive psychology, there has been a significant shift in the focus of mental health research and practice. Positive psychology recognizes happiness and wellbeing as “essential human skills” (Davidson et al., 2005).

Positive psychology helps in understanding how we can enhance our internal capabilities and make the best of our present. Rather than focusing on symptomatic therapy and treatment, positive psychology centers around emotional stability, expectation management, and fruitful thinking, which is why it has been referred to as the “study of ordinary strengths and virtues” (Sheldon & King, 2001).

Positive psychology goes hand in hand with traditional mental health interventions. In this article, we will explore the association between positive psychology and mental health.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- A Look at the Neuroscience of Mental Health

- Using Positive Psychology in Mental Health Counseling

- 4 Positive Psychology Interventions Used in Mental Health Counseling

- Positive Psychology vs. Clinical Psychology

- Research on Positive Psychology and Wellbeing

- Mental Health Interventions That Promote Wellbeing

- 5 Positive Actions That Improves Mental Health

- A Take-Home Message

- References

A Look at the Neuroscience of Mental Health

Mental health disorders affect a great deal of the world population today. And the root of these troubles lies in our brain – the study of which is called neuroscience (Kessler et al., 2009).

Neuroscience suggests which parts of the brain are responsible for causing which behaviors, and how we can address them. It helps us understand the molecular changes that the brain undergoes in different psychotic and neurotic conditions (Kessler et al., 2009).

Stein et al. (2015) assessed how neuroscience has been effectively incorporated in treating mental health issues across all ages and cultural backgrounds.

Neural connections can provoke negative thoughts, actions, and emotions. By understanding the neuroscience behind psychological phenomena (for example, what happens in the brain when we experience trauma or which parts of the cortex gets activated due to mood disorders) psychologists may be better able to manage their client’s issues and delve into a deeper level of treatment.

Neuroscience aims to make mental health interventions focused and evidence-based. For example, individuals with schizophrenia may experience problems with cognitive functioning, which may prevent them from getting back to their usual lives or performing daily life activities.

Neuroscience research has helped professionals realize this and target cognitive repair as an essential part of treating people with schizophrenia improving their prognosis (Barch, 2005).

Incorporating neuroscience in mental health treatment has had numerous benefits.

- Neuroscience makes it easier for therapists and professionals to dig into the root causes of disorders.

- It helps promote mental wellbeing, happiness, and quality of life.

- Neuroscience paves the way for early diagnosis and a brighter prognosis.

- It helps explain the relationship between the mind and the body with more accuracy.

- Neuroscientific research extends research on mental health and happiness.

Portugal et al. (2013) explored the neuroscience of exercise and its impact on mental health, finding that an active lifestyle has dominant effects on our mental faculties. The researchers focused on the relationship between physical activity, mental health disorders like major depression and dementia, and mood changes.

The target population for this study was mainly athletes; however, the results extended to others as well. The research brought light to the fact that regular exercise increases physical and mental strength. It enhances mood, regulates emotions, and maintains optimum bodily functions (Portugal et al., 2013).

The authors argued that physical exercise may be one reason athletes are more resilient in their personal lives – both emotionally and physically.

Using Positive Psychology in Mental Health Counseling

Positive psychology researchers have devised measures such as the Psychological Wellbeing Scale and the Happiness Scale which objectively measure how satisfied a person is with their life. With the advent of these psychological wellbeing measures, mental health professionals found a solid reason to shift their focus from problems to solutions.

Positive psychologist began paying more attention to building on positive behaviors and traits already present in individuals. Positive psychology interventions aim to boost positive emotions and help clients find meaning in life.

The effects of positive psychology interventions last longer and produce more happiness than traditional psychotherapies. A web-based survey on positive psychotherapy in treating major depression revealed that individuals responded sooner and showed signs of recovery with positive interventions (Seligman et al., 2006).

The investigators also agreed that using techniques that enhance positive emotions and build fundamental motivation often leads to a better prognosis than medication alone or traditional psychotherapy (Seligman et al., 2006). The goal of any intervention in mental health counseling should be to shift the individual’s focus from the negative symptoms to the brighter aspects of their life, and positive psychology provides the impetus to bring this change.

4 Positive Psychology Interventions That Are Used In Mental Health Counseling

Substantial evidence proves the effectiveness of positive psychology interventions in psychotherapy and counseling.

In addition to boosting happiness and confidence, it restores the mental balance that we need to sustain a healthy life (Hefferon & Boniwell, 2011).

The advent and awareness of positive psychology interventions in counseling have taken mental health treatment to a diverse multicultural and humanistic level (Magyar-Moe et al., 2015). Whether they’re used in school counseling, individual therapy, or life coaching sessions, positive psychology interventions are now an integral part of mental health treatment. Here are some of the popular PPIs that many psychologists use today:

1. Strengths-based therapy

Strengths-based strategies combine positivity, social psychology, preventive measures, solution-focused methods, and personal development (Rashid, 2015; Smith, 2006). Strengths-based interventions are based on the idea that wellbeing and welfare are critical factors to focus on regardless of the presence or absence of psychological illness.

Strengths-based techniques help find individuals’ strengths and act on them with focused attention (Jones-Smith, 2011).

Strength-oriented techniques include:

- Solution-focused therapies, including conversations, objective tests, and group sessions. The therapist and the client focus on how to accept negative experiences for a better outcome (De Jong & Berg, 2002).

- Case management that focuses on understanding the capabilities of the person.

- Family support and individual supportive counseling.

- Narrating encouraging stories of resilience and positivity that might inspire the individual.

2. Quality of life therapy

The quality of life measure works on the principles of positive psychology and cognitive therapy (Frisch, 2006). It helps clients discover their goals in life and motivates them to follow their dreams and look inside for finding a deeper meaning of self-satisfaction. Therapy focusing on quality of life may use measures like the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI) and CASIO model of self-satisfaction.

3. Hope therapy

As a positive psychology intervention, hope therapy operates on the theory of hope which suggests that emotions can be evaluated or changed according to fruitful goal pursuits (Lopez et al., 2000; Snyder, 2002).

Hope therapy aims to promote a hopeful attitude among clients who are struggling.

The goal of hope therapy is to enhance insight and help individuals reconnect with their sense of self. It uses a semi-structured format, blending standardized tests with subjective ones, and involves four steps:

- Finding hope

- Establishing a connection with it

- Enhancing it

- Following it

Studies measuring the efficacy of hope therapy techniques revealed that individuals who received an auxiliary hope-based intervention in their therapy sessions had higher scores on self-esteem and confidence scales, better clarity of their goals and more energy to act on them (Feldman & Kubota, 2015).

4. Wellbeing therapy

The wellbeing therapy model owes its roots to Ryff and Singer’s (1998) model of psychological wellbeing. Their model was multidimensional, including factors like environmental mastery, personal satisfaction, a more profound sense of meaning in life, acceptance, resilience, and positive social connections (Eren & Kılıç, 2017).

Later, Giovanni Fava, a renowned psychologist and clinical practitioner, developed wellbeing therapy as an effective positive psychology intervention (Ruini & Fava, 2004).

Wellbeing therapy promotes happiness by letting clients identify their thought blocks. Wellbeing therapy is useful as a relapse or prevention management intervention and uses techniques such as (Fava, 1999):

- Writing about significant life experiences and the emotions associated with them.

- Identifying negative thoughts using active communication with the therapist or counselor.

- Challenging negative thoughts with the help of the therapist and planning practical ways to overcome them.

- Growing a positive attitude towards the self by accepting, forgiving, and integrating.

- Encouraging positive actions such as self-expression, journaling, active communication, and an overall healthy lifestyle.

Positive Psychology vs. Clinical Psychology

Positive psychology emerged after a fair share of debate and misunderstanding about how well it can coexist with clinical or health psychology. We know that clinical psychology aims to address mental health issues and apply existing theories and evidence into practice.

Positive psychology promotes wellbeing and happiness, whether or not there is a mental health condition involved (Steffen et al., 2015).

Csikszentmihalyi and Seligman (2000) suggested that focusing on reducing symptoms and restoring normalcy is only a partial solution to a mental health problem. Positive psychology aims to nurture inner happiness and contentment in the individual rather than focusing on addressing deficits.

While clinical psychology digs into the root cause of the illness to help the person recover, positive psychology delves into the root causes of happiness that can bolster a person against negative experiences. Positive psychology is for the most part present and future-oriented. It focuses on a person’s strength, abilities, talents, relationships, positive emotions, positive experiences, and intrinsic motivation.

Clinical psychology and positive psychology do not oppose each other. Both fields target human welfare and wellbeing. Seligman (1998) suggested that positive psychology is not a contemporary addition; it has always been an essential component of humanistic approaches.

While historically, clinical psychology practice was limited primarily to help-seekers and those who were already experiencing mental health challenges, positive psychology reaches out to everyone – those with and without clinical diagnoses.

| Clinical Psychology and Positive Psychology – A Brief Comparative Analysis | |

|---|---|

| Clinical Psychology | Positive Psychology |

| 1. Focuses on symptoms and challenges to reach a solution. | 1. Focuses on positive thoughts, emotions, and actions to reach a solution. |

| 2. Aims to validate theories and put pieces of evidence together to explain and treat a mental condition. |

2. Aims to promote happiness and operates on principles that support wellbeing. |

| 3. Digs into the past to explore the causal factors. | 3. Explores the present and the future to find better ways of living. |

| 4. Includes areas like education, learning disabilities, depression, stress, addiction, trauma, etc. |

4. Includes areas of strength, virtues, talents, abilities, and self-enhancement. |

| 5. Operates in the presence of a problem. | 5. Operates with or without psychopathology. |

| 6. Is preventive and recovery-oriented. | 6. Is preventive and precautionary. |

Research on Positive Psychology and Wellbeing

1. A study on mental illness and wellbeing

Slade (2010), asserted that mental health services now prioritize individual happiness and ways to enhance it.

The prime focus of this research suggested how mental health practitioners can incorporate positive psychology interventions to shift the goal from treating illness to promoting eudaemonia (Coleman, 1999; Slade, 2010). Slade (2010) asserted that the focus of psychiatric or psychological interventions should be on expanding prosperity.

Pointing to Seligman’s research, Slade (2010) suggested that positive psychology values individual experiences, emotions, and actions. It operates at two levels: the personal level (involving awareness of positive traits like love, empathy, forgiveness, and hope) and the social or group level (including interventions to promote social relationships, social responsibilities, tolerance, altruism, and a sense of values).

By following the positive psychology approaches, Slade (2010) advised mental health researchers and practitioners to focus more on the overall enhancement of an individual, rather than concentrating only on the problem areas.

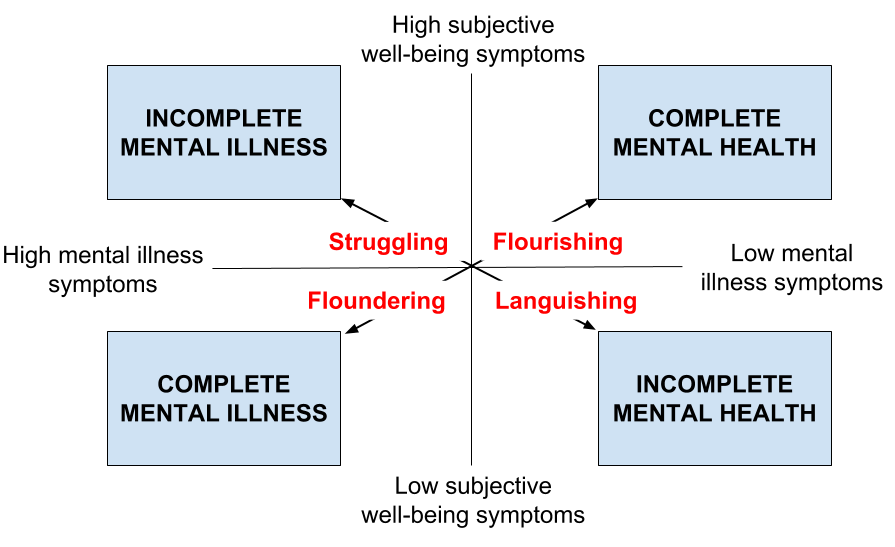

2. The complete state model of mental health

Slade (2010) developed the complete state model (CSM) of mental health from a salutogenic view point. The CSM is also known as the dual-factor model of mental health (Suldo & Shaffer, 2008) and the two-continua model of mental health (Westerhof & Keyes, 2010).

The CSM identifies mental wellbeing and mental illness on a continuum from present to absent, and from high to low (Keyes, 2005).

The interplay of these two factors determines a person’s overall mental health.

The CSM identifies mental health as having a high level of wellbeing and low level of mental illness (e.g., depression, anxiety, stress). The focus here is not on ignoring mental illness or symptoms, but on suggesting that wellbeing and mental illness are separate issues that together structure our mental health.

The absence of psychopathology does not imply sound mental health unless the person has a high state of psychological wellbeing. The CSM explanation approved of positive psychology for being significantly relevant to personal wellbeing and recovery.

Positive psychology works around the concepts of happiness, hope, motivation, empathy, and self-esteem, all of which directly contributes to enhancing our wellbeing (Schrank & Slade, 2007).

It promotes authentic happiness and describes that a good life can come in four forms:

- The pleasant life

Consisting of positive emotions and the drive to do things that enhance pleasure and self-satisfaction. - The engaged life

Where a person preoccupies themself with deeper insight into their emotions and character strengths and models their life accordingly. - The meaningful life

In which the individual achieves a heightened sense of self and seeks the true meaning of happiness. - The achieving life

Where a person is driven to work harder and dedicate themself to achieving their ambitions. In an achieving life, a person derives happiness and a true sense of self from acting on their dreams and making them successful.

3. Positive psychology and health

The World Health Organization described health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and is not merely the absence of illness or infirmity” (cited in Park et al., 2016).

Researchers and health professionals all over the world have recognized the importance of eudaemonia, an optimal state of functioning, and positive mental states for sound physical health (Ryff & Singer, 1998).

Cohen et al. (2003) found that participants who reported experiencing positive emotions like happiness, satisfaction, and enthusiasm, had lower risks of catching a cold virus than participants who reported feelings of depression, loneliness or anger, suggesting that positive emotions facilitate better health, more immunity, and stronger resilience.

Kim et al. (2013) also found that having a firm purpose in life reduced the risk of coronary diseases in patients. Patients with a history of cardiac dysfunctions showed quick recovery and lower chances of relapse when treated with positive interventions.

Mental Health Interventions That Promote Wellbeing

1. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most popular forms of psychotherapy in use today. It is aligned with personal wellness and self-recovery.

CBT is by and large a psychosocial therapy. The client is as responsible for their recovery as the therapist is. CBT helps build personal strengths and resilience by reinforcing positive thinking, self-driven actions, and enough space for self-expression (Kuyken et al., 2011).

The basic principle of CBT is that our thoughts are the root cause of our troubles, and it attempts to modify how we think, feel, and act, with the ultimate goal of pumping up self-awareness.

CBT has been proven effective in treating depression, anxiety, and mood disorders (e.g., Chambless & Ollendick, 2001; DeRubeis & Crits-Christoph, 1998).

The core principle of CBT is developing a self-driven attitude among individuals, where they can bring the change that they want in life.

2. Mindfulness

Mindfulness, or the art of being present in the moment, is a cluster of positive techniques that promote wellbeing and inner peace. With roots embedded in ancient Buddhism and yogic practices, mindfulness spreads the message of dwelling in the ‘now’ and getting rid of what has been.

Mindfulness has been used to treat an array of mental health conditions and helps in mood management, lifestyle modification, aftercare for posttraumatic stress disorder, and emotional support counseling (Ackerman, 2017).

Mindfulness-based positive interventions increase subjective feelings of wellness and are beneficial for both the clinical and the non-clinical population (Grossman et al., 2004).

Niemiec (2013) clearly explained the link between mindfulness and personal strengths, character building, and positive outcomes. He indicated that mindful positive interventions that build intrinsic motivation and supports our overall wellbeing include mindfulness-based strength practice (MBSP), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), and mindfulness-based meditation practices.

3. Narrative psychotherapy

Narrative psychotherapy draws on the power of self-expression and encompasses three aspects (Smyth, 1998):

- No inhibition to express or say what we feel.

- Cognitive awareness of what we think and feel.

- Social awareness of how we say what we feel.

Narrative psychotherapy approaches involve asking individuals to write about their emotional experiences, identify negative thoughts and replace them. Some narrative psychotherapies encourage participants to make a story based on their personal experiences and think about how they can transform the negative consequences to positive ones.

Narrative psychotherapy benefits people who lack self-expression or are introverts by nature, people with high levels of aggression, and those who are struggling with anger management (Christensen & Smith, 1993).

4. Reminiscence therapy

Reminiscence therapy (RT) stands out among traditional positive interventions that promote wellbeing through present or future-oriented exercises. Dr. Robert Butler (1960), a geriatric psychiatrist, promoted the idea that recollecting memories can be therapeutic.

Butler (1960) argued that reminiscing about old memories, especially for people who are nearing death or experiencing severe depression, allows them to put their lives in perspective. It is not about looking back. It is about finding the meaning of the ‘now’ through what has already been.

Reminiscence therapy aims to boost self-esteem and a sense of fulfillment in the individual. For older people, reminiscing about their past may motivate them to speak and share their experiences with the therapist, thereby fostering self-expression and emotional catharsis.

Besides benefiting the older population, RT is also a treatment of choice for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, where patients are given cues of information to recall what they remember. Reminiscence therapy aims to cultivate happiness and positivity.

- It encourages participants to talk about their past and share their feelings.

- The active listening skills of the therapist help make the client feel heard and important.

- The informal therapy setting motivates the clients to open up and participate in active communication.

- RT, when conducted as group therapy, lets individuals listen to each other’s stories and expand their perception.

- It promotes social communication and increased positive interactions.

We can build a state of wellbeing with positive psychology

5 Positive Actions That Improves Mental Health

Ben-Shahar (2007) explained that practicing positivity is the real pursuit of happiness and nurtures lifelong satisfaction. His works on the science of happiness indicate that we can recraft our lives with some simple positive interventions, such as:

1. Counting your blessings

Making a list of the things that make us happy and the people who mean the most to us brings a sense of meaning and fulfilment in our lives (Diener & Diener, 1996).

The practice is simple (Martínez-Martí et al., 2010):

- List the things that you love doing. These are called ‘happiness boosters’ and can include spending time with family, doing crafts, or working (among others).

- Think about why you feel blessed when you perform those tasks.

- Imagine what life would be like in the absence of those things and how you would feel if you could no longer spend time on them. Write your feelings down.

- Next, ask yourself, how much time you spend on the happiness boosters and make a list of the things that you think prevent you from doing more of what you love.

- Learn from your responses and aim to enhance the happiness boosters by engaging in activities that you love.

2. Learning from negative experiences

Negative encounters can teach us plenty of positive life lessons. Ben-Shahar (2007) has found that past experiences make a person more resilient to stress, and once we overcome the adversity, we become more appreciative of the life that we have now.

3. Practicing gratitude

Gratitude is a powerful tool. Start by listing the people and the things you are grateful for taking a moment to express your thankfulness to someone verbally. Daily gratitude practices may include gratitude journaling, gratitude visits, or gratitude notes.

4. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle

While it is true that happiness can improve our lifestyle, research has also proved that a healthy lifestyle can cultivate happiness. Ben Shahar (2007) found that a positive lifestyle acts as a natural healing mechanism.

Individuals who had a healthy lifestyle (including a healthy diet, good sleep, and regular exercise), showed less susceptibility to diseases and psychological distress (Trudel-Fitzgerald et al., 2018).

5. Monitoring mood

Mood is the thread that links our thoughts and actions. We know how we are feeling by gauging our mood states. Creating a personal mood chart can be a great way to keep track of the ups and downs in our mood and understand why we feel the way we do.

Making a mood chart is fun and straightforward. You only have to be true to yourself and make honest notes about your feelings throughout the day. Set aside a few minutes every day to fill in your mood journal and notice how it guides you to better self-understanding.

A Take-Home Message

The happiness we seek may already be there within us. All we need to do is slow down and take a moment to look for it.

Positive psychology paves the way for us to pause and appreciate the wonders that are already in our lives. It does not contradict or contrast traditional mental health practices but rather complements them by changing our thoughts and actions for the better (Ben-Shahar, 2007).

The goals of positive psychology interventions are to explore pleasure, the joy of connecting with others, and a deeper sense of meaning in life.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Ackerman, C. (2017, Mar). PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved from https://positivepsychology.com/benefits-of-mindfulness/.

- Barch, D. M. (2005). The cognitive neuroscience of schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 321-353.

- Ben-Shahar, T. (2007). Happier: Learn the secrets to daily joy and lasting fulfillment (vol. 1). McGraw-Hill.

- Butler, R. N. (1960). Intensive psychotherapy for hospitalized aged. Geriatrics, 15, 644-653.

- Chambless, D. L., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001). Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 685-716.

- Christensen, A. J., & Smith, T. W. (1993). Cynical hostility and cardiovascular reactivity during self-disclosure. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55(2), 193-202.

- Cohen, S., Doyle, W. J., Turner, R. B., Alper, C. M., & Skoner, D. P. (2003). Emotional style and susceptibility to the common cold. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(4), 652-657.

- Coleman, P. G. (1999). Creating a life story: The task of reconciliation. The Gerontologist, 39, 133-139.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Seligman, M. (2000). Positive psychology. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5-14.

- Davidson, L., Sells, D., Songster, S., & O’Connell, M. (2005). Qualitative studies of recovery: What can we learn from the person? In R. O. Ralph & P. W. Corrigan (Eds.), Recovery in mental illness: Broadening our understanding of wellness (pp. 147-170). American Psychological Association.

- De Jong, P., & Berg, I. S. (2002). Interviewing for solutions (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole.

- DeRubeis, R. J., & Crits-Christoph, P. (1998). Empirically supported individual and group psychological treatments for adult mental disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 37-52.

- Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181-185.

- Eren, H. K., & Kılıç, N. (2017). Well-being therapy. MOJ Addiction Medicine & Therapy, 4(2), 249-251.

- Fava, G. A. (1999). Well-being therapy: Conceptual and technical issues. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68(4), 171-179.

- Feldman, D. B., & Kubota, M. (2015). Hope, self-efficacy, optimism, and academic achievement: Distinguishing constructs and levels of specificity in predicting college grade-point average. Learning and Individual Differences, 37, 210-216.

- Frisch, M. B. (2006). Quality of life therapy: Applying a life satisfaction approach to positive psychology and cognitive therapy. Wiley.

- Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35-43.

- Gruman, J. A., Schneider, F. W., & Coutts, L. M. (2017). Applied social psychology: Understanding and addressing social and practical problems. Sage.

- Hefferon, K., & Boniwell, I. (2011). Positive psychology: Theory, research and applications. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Jones-Smith, E. (2011). Spotlighting the strengths of every single student: Why US schools need a new, strengths-based approach. ABC-CLIO.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Chatterji, S., Lee, S., Ormel, J., Ustün, T. B., & Wang, P. S. (2009). The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 18(1), 23-33.

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539-548.

- Kim, E. S., Sun, J. K., Park, N., Kubzansky, L. D., & Peterson, C. (2013). Purpose in life and reduced risk of myocardial infarction among older US adults with coronary heart disease: A two-year follow-up. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(2), 124-133.

- Kuyken, W., Padesky, C. A., & Dudley, R. (2011). Collaborative case conceptualization: Working effectively with clients in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Guilford Press.

- Lopez, S. J., Floyd, R. K., Ulven, J. C., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Hope therapy: Helping clients build a house of hope. In C. R. Snyder (Ed.), Handbook of hope (pp. 123-150). Academic Press.

- Magyar-Moe, J. L., Owens, R. L., & Conoley, C. W. (2015). Positive psychological interventions in counseling: What every counseling psychologist should know. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(4), 508-557.

- Martínez-Martí, M. L., Avia, M. D., & Hernández-Lloreda, M. J. (2010). The effects of counting blessings on subjective well-being: A gratitude intervention in a Spanish sample. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 886-896.

- Niemiec, R. M. (2013). Mindfulness and character strengths. Hogrefe.

- Park, N., Peterson, C., Szvarca, D., Vander Molen, R. J., Kim, E. S., & Collon, K. (2016). Positive psychology and physical health: Research and applications. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 10(3), 200-206.

- Pliszka, S. R. (2016). Neuroscience for the mental health clinician. Guilford Press.

- Portugal, E. M. M., Cevada, T., Monteiro-Junior, R. S., Guimarães, T. T., da Cruz Rubini, E., Lattari, E., Blois, C., & Deslandes, A. C. (2013). Neuroscience of exercise: From neurobiology mechanisms to mental health. Neuropsychobiology, 68(1), 1-14.

- Rashid, T. (2015). Positive psychotherapy: A strength-based approach. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 25-40.

- Ruini, C., & Fava, G. A. (2004). Clinical applications of well-being therapy. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 371-387). Wiley.

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The role of purpose in life and personal growth in positive human health. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Schrank, B., & Slade, M. (2007). Recovery in psychiatry. Psychiatric Bulletin, 31(9), 321-325.

- Seligman, M. (1998). Building human strength: Psychology’s forgotten mission. Monitor. APA Monitor, 29(1), 2-3.

- Seligman, M. E., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 61(8), 774-788.

- Sheldon, K. M., & King, L. (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist, 56(3), 216-217.

- Slade, M. (2010). Mental illness and well-being: The central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 10(1), 1-14.

- Smith, E. J. (2006). The strength-based counseling model. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(1), 13-79.

- Smyth, J. M. (1998). Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(1), 174-184.

- Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4), 249-275.

- Steffen, E., Vossler, A., & Stephen, J. (2015). From shared roots to fruitful collaboration: How counselling psychology can benefit from (re)connecting with positive psychology. Counselling Psychology Review, 30(3), 1-11.

- Stein, D. J., He, Y., Phillips, A., Sahakian, B. J., Williams, J., & Patel, V. (2015). Global mental health and neuroscience: Potential synergies. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(2), 178-185.

- Suldo, S. M., & Shaffer, E. J. (2008). Looking beyond psychopathology: The dual-factor model of mental health in youth. School Psychology Review, 37(1), 52-68.

- Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., Boehm, J. K., Tworoger, S. S., & Kubzansky, L. D. (2018). Being happier may lead to better health: Positive psychological well-being and lifestyle over 20 years of follow-up. International Positive Psychology Association Recent Research: Recaps & Insights, 1(1).

- Vaillant, G. E. (2009). The natural history of alcoholism revisited. Harvard University Press.

- Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 17(2), 110-119.

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

It made me realise that I actually belong to the happy team! What matters is to spread happiness around, and help as many people as possible to experience it!

Thank you, Madhuleena!

Hi Madhuleena…I just love your article. It is very informative and interesting

Very useful~