The Theories of Emotional Intelligence Explained

Emotional Intelligence, or, what is commonly referred to as EQ has been claimed to be the key to success in life!

Emotional Intelligence, or, what is commonly referred to as EQ has been claimed to be the key to success in life!

Despite the fact that theories of emotional intelligence only really came about in 1990, much has been written about this topic since then.

It has been argued by some people that EQ, the ‘emotion quotient’, is even more important than the somewhat less controversial ‘intelligence quotient’ or IQ.

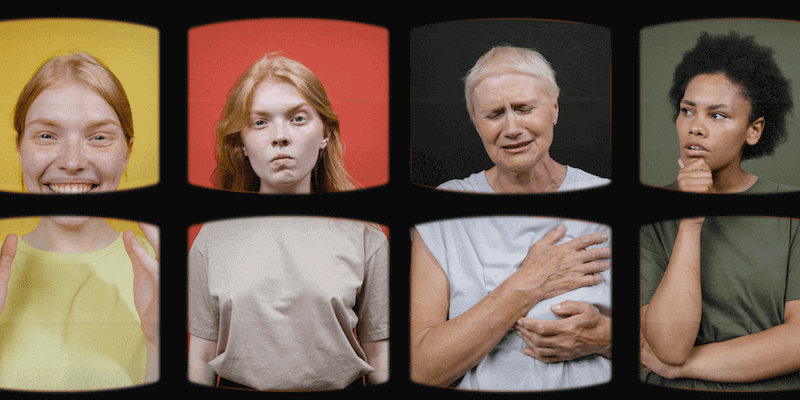

Why bother studying EQ? Well, can you imagine a world in which you didn’t understand any of your feelings? Or where you couldn’t perceive that another person was angry with you by the ferocious look on their face? It would be a nightmare!

Emotional intelligence is everywhere we look, and without it, we would be devoid of a key part of the human experience.

This article aims to share theories of emotional intelligence, and the 5 components of emotional intelligence will be discussed.

It is also hoped that some of your questions about emotional intelligence, such as “does emotional intelligence involve specific competencies?” and “is emotional intelligence linked to personality traits?” will be answered. Please enjoy!

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will not only enhance your ability to understand and regulate your emotions but will also give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What are the 5 Components of Emotional Intelligence?

- Models and Frameworks of the Emotional Intelligence Concept

- Research on EQ Characteristics

- Does EI involve Specific Competencies?

- Is EI linked to Personality Traits?

- A Closer Look at EI and Personality

- Different Types of Emotional Intelligence

- Dimensions of the Concept

- 12 Recommended Research Articles and Papers on EI

- Key Topics in Emotional Intelligence Research

- Are There Gender Differences in Emotional Intelligence?

- Role of EQ in Self-awareness

- The Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence

- Emotional Intelligence and the Brain: Advancements in Neuroscience

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What are the 5 Components of Emotional Intelligence?

What is meant when we refer to emotional intelligence? Well, let’s begin with a look at ‘intelligence’. Intelligence refers to the unique human mental ability to handle and reason about information (Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008).

Thus, emotional intelligence (EI):

“concerns the ability to carry out accurate reasoning about emotions and the ability to use emotions and emotional knowledge to enhance thought”

(Mayer et al., 2008, p. 511).

According to almost three decades of research, emotional intelligence (EI) results from the interaction of intelligence and emotion (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2004). EI refers to an individual’s capacity to understand and manage emotions (Cherry, 2018).

What are the five components of EI?

The notion of EI consisting of five different components was first introduced by Daniel Goleman, a psychologist and bestselling author.

[Reviewer’s Update]

Daniel Goldman, who received his PhD in psychology from Harvard and cofounded the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning at Yale’s Child Studies Center, expanded the four branches of Mayer et al.’s (2004) emotional intelligence model (included in more detail below, they are: identifying emotions on a nonverbal level, using emotions to guide cognitive thinking, understanding the information emotions convey and the actions emotions generate, and regulating one’s own emotions) to include emotional self-awareness, self-regulation, social skills, empathy, and motivation (Resilient Educator, 2020).

The five components of EI are (Cherry, 2018):

1. Self-awareness

Self-awareness refers to the capacity to recognize and understand emotions and to have a sense of how one’s actions, moods and the emotions of others take effect.

It involves keeping track of emotions and noticing different emotional reactions, as well as being able to identify the emotions correctly.

Self-awareness also includes recognizing that how we feel and what we do are related, and having awareness of one’s own personal strengths and limitations.

Self-awareness is associated with being open to different experiences and new ideas and learning from social interactions.

2. Self-regulation

This aspect of EI involves the appropriate expression of emotion.

Self-regulation includes being flexible, coping with change, and managing conflict. It also refers to diffusing difficult or tense situations and being aware of how one’s actions affect others and take ownership of these actions.

3. Social skills

This component of EI refers to interacting well with other people. It involves applying an understanding of the emotions of ourselves and others to communicate and interact with others on a day-to-day basis.

Different social skills include – active listening, verbal communication skills, non-verbal communication skills, leadership, and developing rapport.

4. Empathy

Empathy refers to being able to understand how other people are feeling.

This component of EI enables an individual to respond appropriately to other people based on recognizing their emotions.

It enables people to sense power dynamics that play a part in all social relationships, but also most especially in workplace relations.

Empathy involves understanding power dynamics, and how these affect feelings and behavior, as well as accurately perceiving situations where power dynamics come into force.

5. Motivation

Motivation, when considered as a component of EI, refers to intrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic motivation means that an individual is driven to meet personal needs and goals, rather than being motivated by external rewards such as money, fame, and recognition.

People who are intrinsically motivated also experience a state of ‘flow’, by being immersed in an activity.

They are more likely to be action-oriented, and set goals. Such individuals typically have a need for achievement and search for ways to improve. They are also more likely to be committed and take initiative.

This has been a brief introduction into the 5 components of Emotional Intelligence: self-awareness, self-regulation, social skills, empathy, and motivation.

5 Components of emotional intelligence… in 60 seconds – Online PM Courses – Mike Clayton

Models and Frameworks of the Emotional Intelligence Concept

What is EI? Hopefully, through discussing its’ components, the picture is becoming clearer.

The early theory of emotional intelligence described by Salovey and Mayer in 1990 explained that EI is a component of Gardner’s perspective of social intelligence.

Similar to the so-called ‘personal’ intelligences proposed by Gardner, EI was said to include an awareness of the self and others (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). One aspect of Gardner’s conception of personal intelligence relates to ‘feelings’ and this aspect approximates what Salovey and Mayer conceptualize as EI (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

What differentiates EI from the ‘personal’ intelligences is that EI does not focus on a general sense of self and the appraisal of others – rather, it is focused on recognizing and using the emotional states of the self and others in order to solve problems and regulate behavior (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

What about proposed models of EI? Faltas (2017) argues that there are three major models of emotional intelligence:

- Goleman’s EI performance model

- Bar-On’s EI competencies model

- Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso’s EI ability model

These three models have been developed from research, analysis, and scientific studies. Now, let’s examine each of these in more detail…

Goleman’s EI Performance Model (Faltas, 2017)

According to Goleman, EI is a cluster of skills and competencies, which are focused on four capabilities: self-awareness, relationship management, and social awareness. Goleman argues that these four capabilities form the basis of 12 ‘subscales’ of EI.

He suggests that these subscales are:

- emotional self-awareness

- emotional self-control

- adaptability

- achievement orientation

- positive outlook

- influence

- coaching and mentoring

- empathy

- conflict management

- teamwork

- organizational awareness

- inspirational leadership

Goleman developed these 12 subscales from research into EI in the workforce.

Bar-On’s EI Competencies Model (Faltas, 2017)

Bar-On put forward the suggestion that EI is a system of interconnected behavior that arises from emotional and social competencies. He argues that these competencies have an influence on performance and behavior.

Bar-On’s model of EI consists of five scales: self-perception, self-expression, interpersonal, decision-making, and stress management. You will be noticing the similarities that are appearing in these models of EI!

Bar-On also proposed 15 subscales of the EI concept:

- self-regard,

- self-actualization,

- emotional self-awareness,

- emotional expression,

- assertiveness,

- independence,

- interpersonal relationships,

- empathy,

- social responsibility,

- problem-solving,

- reality testing,

- impulse control,

- flexibility,

- stress tolerance and

- optimism.

According to Bar-On, these competencies, as components of EI, drive human behavior and relationships.

Mayer, Salovey and Caruso’s EI Ability Model (Faltas, 2017)

This model suggests that information from the perceived understanding of emotions and managing emotions is used to facilitate thinking and guide our decision making. This EI framework emphasizes the four-branch model of EI.

The four-branch model

Mayer and colleagues (2004) developed the four-branch ability model of EI.

They suggest that the abilities and skills of EI can be divided into 4 areas – the ability to:

- Perceive emotion (1)

- Use emotion to facilitate thought (2)

- Understand emotions (3), and

- Manage emotion (4).

These branches, which are ordered from emotion perception through to management, align with the way in which the ability fits within the individual’s overall personality (Mayer et al., 2004).

In other words, branches 1 and 2 represent the somewhat separate parts of information processing that are thought to be bound in the emotion system – whereas, emotion management (branch 4) is integrated into his/her plans and goals (Mayer et al., 2004).

Also, each branch consists of skills that progress developmentally from more basic skills through to more sophisticated skills.

Let’s examine each branch:

- This branch involves the perception of emotion, including being able to identify emotions in the facial and postural expressions of others. It reflects non-verbal perception and emotional expression to communicate via the face and voice (Mayer et al., 2004).

- Branch 2 includes the ability to use emotions in order to aid thinking.

- This branch represents the capacity to understand emotion, including being able to analyze emotions and awareness of the likely trends in emotion over time, as well as an appreciation of the outcomes from emotions. It also includes the capacity to label and discriminate between feelings.

- This branch, emotional self-management, includes an individual’s personality with goals, self-knowledge and social awareness shaping the way in which emotions are managed (Mayer et al., 2004).

According to Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey (2016), these skills are what define EI.

In 2016, based on the developments in EI research, Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey updated the four-branch model. They included more instances of problem-solving and claimed that the mental abilities involved in EI do, in fact, remain to be determined (Mayer et al., 2016).

Mayer and colleagues suggested that EI is a broad, ‘hot’ intelligence (2008). They include practical, social and emotional intelligence in their understanding of ‘hot’ intelligences.

So-called ‘hot’ intelligences are those in which people engage with subject matter about people (Mayer et al., 2016). Mayer et al. (2016) invite comparison of EI with the personal and social intelligences and they contend that EI can be positioned among these other ‘hot intelligences’.

It was argued that the specific abilities that EI consists of are specific forms of problem-solving (Mayer et al., 2016).

The four-branch model can be measured using the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT).

Research on EQ Characteristics

In the 1960s, the term EI was used incidentally in psychiatry and literary criticism (Mayer et al., 2004).

However, it was formally introduced to the landscape of psychology in 1990 by Mayer and colleagues (Mayer et al., 2004). Mayer et al. published a few articles in which EI was clearly defined, and a theory plus a measure of EI was developed. Since 1990, research into the characteristics of EQ has grown.

EQ and Academia

A number of studies have looked at predicting grades at school and intellectual problem-solving in relation to EQ (Mayer et al., 2004). It has been shown that the correlation between EI and grades of college students is between r = .20 and .25 (Mayer et al., 2004).

One study of gifted students in Israel found that they scored more highly on EI than those students who were not so academically gifted.

However, the incremental prediction of EI and general intelligence has only been modest to slight (Mayer et al., 2004).

Interestingly, when the study focused on emotion-related tasks in 90 graduate psychology students, a positive relationship was found between Experiencing Emotion and both GPA and the year the student was up to in the program (Mayer et al., 2004).

EQ and Deviancy/Problem Behavior

Even when both intelligence and personality variables are controlled for statistically, EI is inversely related to bullying, violence, tobacco use and drug problems (Mayer et al., 2004).

For example, one study showed that EI was negatively related to student-rated aggression. In 2002, Swift studied the EI of 59 individuals who were part of a court-ordered violence-prevention program, and it was found that Perceiving Emotions was negatively related to psychological aggression (which took the form of insults and emotional torment) (Mayer et al., 2004).

However, surprisingly, Swift also found that rates of psychological aggression were actually associated with higher scores in Managing Emotion! (Mayer et al., 2004).

EQ and Success

It has been previously suggested that EQ is the most important determinant of success in life. Whilst this is not necessarily true, EI has nevertheless been related to success (Cherry, 2018).

Research has found an association between EI and a broad range of skills such as making decisions or achieving academic success (Cherry, 2018).

EQ and Development

EI has been increasingly studied in samples of children and adolescents (Mayer et al., 2008).

EI has been shown to consistently predict positive social and academic outcomes in children (Mayer et al., 2008). A longitudinal study of three to four-year-old children conducted by Denham et al. (2003) used ratings of children’s emotional regulation and emotion knowledge.

Higher levels of emotional regulation and emotion knowledge predicted social competence at ages three to four and then, later, in kindergarten.

EQ and Perceptions

A range of studies has found that those with high levels of EI are actually perceived more positively by other people (Mayer et al., 2008).

EQ and Wellbeing

EI has been found to correlate with enhanced life satisfaction and self-esteem (Mayer et al., 2008). Furthermore, EI correlates with lower ratings of depression (Mayer et al., 2008).

EQ and Pro-social/Positive Behaviors

Research has found a positive correlation between scores in Managing Emotion and the quality of interactions with friends (Mayer et al., 2004).

Individuals scoring more highly on EI have also been shown to be ranked as more liked and valued by members of the opposite sex!

Emotion regulation has been found to predict social sensitivity and the quality of interactions with others (Mayer et al., 2004).

EQ and Leadership/Organizational Behavior

Studies have consistently shown that customer relations are positively influenced by EI (Mayer et al., 2004). Even after personality traits have been controlled for, individuals rated as higher EI generated vision statements of higher quality than others (Mayer et al., 2004).

Does EI involve Specific Competencies?

Yes!

It has been shown that EI does definitely involve specific competencies.

To provide a practical explanation of the specific competencies that EI involves, I will refer to the competencies measured by the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i), and provide examples of what each competency really means (Meshkat & Nejati, 2017).

The EQ-I is a comprehensive self-report measure of EI. The competencies in EI, as measured by the EQ-I, are, as described by Meshkat and Nejati (2017):

- Emotional self-awareness (e.g. “it is hard for me to understand the way I feel”).

- Assertiveness (e.g. “it is difficult for me to stand up for my right”)

- Self-regard (e.g. “I don’t feel good about myself”)

- Independence (e.g. “I prefer others to make decisions for me”)

- Empathy (e.g. “I’m sensitive to the feelings of others”)

- Interpersonal relationships (e.g. “people think that I’m sociable”)

- Social responsibility (e.g. “I like helping people”)

- Problem-solving (e.g. “my approach to overcoming difficulties is to move step by step)

- Reality testing (e.g. “it’s hard for me to adjust to new conditions”)

- Flexibility (e.g. “it’s easy for me to adjust to new conditions”)

- Stress tolerance (e.g. “I know how to deal with upsetting problems”), and

- Impulse control (e.g. “it’s a problem controlling my anger).

As well as these specific competencies, happiness, optimism and self-actualization act to ‘facilitate’ EI (Meshkat & Nejati, 2017).

Is EI linked to Personality Traits?

From a large study of 1584 individuals, Mayer and colleagues (2004) concluded that people who are rated as higher in EI tend to be more agreeable, open and conscientious.

Furthermore, findings from neuroscience have shown that EI also involves the same brain regions that are implicated in conscientiousness (Barbey, Colom, & Grafman, 2014).

The neural findings support the fact that a central feature of EI is conscientiousness, which is characterized by the degree of organization, persistence, control, and motivation in goal-directed behavior (Barbey et al., 2014).

Let’s examine this in some detail.

A Closer Look at EI and Personality

According to their seminal paper on EI in 1990, Salovey and Mayer describe EI as the subset of social intelligence. Researchers Cantor and Kihlstrom have argued that social intelligence is a central construct for understanding personality (Salovey & Mayer, 1990).

Behavior has been described as the observable expression of someone’s personality in a certain social condition (Mayer et al., 2016). Personality includes motives, emotions, social styles, self-awareness and self-control (Mayer et al., 2016).

These components contribute to consistent patterns of behavior, quite distinct from intelligence.

Whilst earlier research mentioned previously has found an association between conscientiousness and EI, in actual fact, more recent findings show that the actual correlation between EI and the ‘Big 5’ personality traits is close to zero!

Research by Mayer and colleagues (2016) found the following correlations between EI and the Big 5:

- Neuroticism – r = -.17

- Openness – r = .18

- Conscientiousness – r = .15

- Extraversion – r = .12

- Agreeableness – r = .25

Thus, whereas previous studies have shown that EI was most closely related to the facet of conscientiousness, more recently the most closely related personality factor to EI was found to be agreeableness.

However, the very low levels of correlation have led researchers to conclude that intelligence and socio-emotional styles are relatively distinct and independent (Mayer et al., 2016).

Nevertheless, personality does seem to relate in some ways to EI.

For example, people who score higher in EI tend to be more likely to prefer social occupations than enterprising occupations, as indicated by the Holland Self-Directed Search (Mayer et al., 2004). In addition, individuals who score more highly on EI also tend to display more adaptive defense mechanisms than less adaptive ones, such as denial (Mayer et al., 2004).

Further research is certainly warranted.

Different Types of Emotional Intelligence

To examine so-called ‘types’ of EI, we can examine what people with high EI have the capacity to do.

For starters, they are able to quickly and accurately solve a range of emotion-related problems (Mayer, 2009). A type of EI is being able to solve emotion-based problems. Those who are high in EI can also perceive emotions in other people’s faces accurately (Mayer, 2009). Therefore, a type of EI is facial perception.

People with high EI have an awareness of how certain emotional states are associated with specific ways of thinking (Mayer, 2009). For example, people high in EI may realize that sadness actually facilitates analytic thinking, so they may, therefore, choose (if possible) to analyze things when they are in a sad mood (Mayer, 2009). Thus a ‘type’ of EI is understanding emotions and how they can drive thinking.

People high in EI have an appreciation of the determinants of an emotion and the associated meaning of the emotion – for example, they may recognize that people who are angry are potentially dangerous, that happiness means people are more likely to want to socialize compared to sad people who are preferring to be alone (Mayer, 2009). Thus, a ‘type’ of EI is being able to ‘read’ emotion.

Highly EI individuals are able to manage the emotions of themselves and others (Mayer, 2009). A ‘type’ of EI is effective emotion management. These individuals also understand that people who are happy are more likely to be willing to attend a social event compared to people who are sad, or afraid – therefore, a type of EI is socio-emotional awareness.

Finally, those high in EI have an appreciation of how emotional reactions unfold, which demonstrates another ‘type’ of EI.

Dimensions of the Concept

When examining the dimensions of EI, it is necessary to differentiate between emotions and EI. Emotions are developed in our environment, resulting from circumstances and knowledge (Faltas, 2017).

Emotion may be described as “a natural instinctive state of mind that derives from our current and past experiences and situations” (Faltas, 2017). Our feelings and things that we experience affect our emotions.

On the other hand, EI is an ability (Faltas, 2017). It is having the awareness, and skill, in order to know, recognize, and understand feelings, moods, and emotions and use them in an adaptive way (Faltas, 2017).

EI involves learning how to manage feelings and emotions and to use this information to guide our behavior (Faltas, 2017). EI drives how we act – including decision-making, problem-solving, self-management and demonstrating leadership (Faltas, 2017).

EI has been shown to be a relatively stable aptitude, as opposed to emotional ‘knowledge’ – which is the sort of information that EI actually uses. EI, in comparison to emotional knowledge, is acquired more readily and can be taught.

In that key paper from 1990, Salovey and Mayer stated that the mental processes related to EI are “appraising and expressing emotions in the self and others, regulating emotion in the self and others, and utilization of emotions in adaptive ways” (p. 190).

EI touches and influences every aspect of our lives (Faltas, 2017). Dimensions of EI, therefore, include driving behavior and affecting decision-making.

Other dimensions of the concept include solving conflicts, and affecting both how we feel about ourselves and also how we communicate with others (Faltas, 2017).

EI affects how we manage the stress that occurs in day-to-day life, as well as how we perform in the workplace and manage and lead teams (Faltas, 2017).

EI has an effect on all areas of our personal and professional development (Faltas, 2017). It helps us to advance, to mature, and to attain our goals (Faltas, 2017).

12 Recommended Research Articles and Papers on EI

- Barchard, K. A. (2003). Does emotional intelligence assist in the prediction of academic success? Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 840-858.

- Brackett, M., Mayer, J. D., & Warner, R. M. (2004). Emotional intelligence and the prediction of behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1387-1402.

- Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: In search of an elusive construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 989-1015.

- Izard, C. E. (2001). Emotional intelligence or adaptive emotions? Emotion, 1(3), 249-257.

- Lopes, P. N., Salovey, P., & Straus, R. (2003). Emotional intelligence, personality, and the perceived quality of social relationships. Personality and individual Differences, 35(3), 641-658.

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267-298.

- Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsades, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 507-536.

- Nathanson, L., Rivers, S. E., Flynn, L. M., & Brackett, M. A. (2016). Creating emotionally intelligent schools with RULER. Emotion Review, 8(4), 305-310.

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2000). On the dimensional structure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(2), 313-320.

- Petrides, K. V., Pita, R., & Kokkinaki, F. (2007). The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 273-289.

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425-448.

- Salovey, P., & Grewal, D. (2005). The science of emotional intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(6), 281-285.

Key Topics in Emotional Intelligence Research

What about the future for EI?

As identified earlier in the article, one area of future research into EI is to clarify the relationship (if any!) between EI and personality traits. You will soon read some research from neuroscience, and this is most certainly another area of EI research that will continue to grow.

The key researchers in EI – Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey – have also put forward two suggestions for further research.

The first is in regards to the so-called ability measures of EI… the factor structure is yet to be clarified (Mayer et al., 2016).

The second area is that, if EI is, in fact, a discrete intelligence, there would need to be a separate reasoning capacity to understand emotions…there is some evidence on this so far: Heberlein and colleagues demonstrated that the areas of the brain that serve to perceive emotional expressions (such as happiness) can be differentiated from the brain areas that are responsible for perceiving expressions of personality (such as shyness) (Mayer et al., 2016).

Are There Gender Differences in Emotional Intelligence?

There has been a wealth of interesting research into whether gender is related to EI.

The following discussion is based on a comprehensive research paper published by Meshkat and Nejati in 2017. Although findings have varied, it appears that there are gender differences in EI. These differences may be attributable to both social and biological factors.

Gender has been described as an inherently social process, and that certain traits are seen as desirable for one gender but not another – for example, assertiveness is a ‘typical’ male characteristic, whilst empathy is seen as a desirable female characteristic.

According to Meshkat and Nejati (2017) males and females are socialized differently – females are encouraged to be cooperative, expressive and tuned in to their interpersonal world, whereas males are encouraged to be competitive, independent and instrumental.

Biologically, females are ‘biochemically adapted’ to focus on the emotions of the self and other as necessary to promote survival. Furthermore, neuroscientifically speaking, the areas of the brain that are necessary for emotional processing are larger in females than these areas are in males.

The cerebral processing of emotions has also been shown to differ between males and females.

Findings of research from around the world into gender differences in EI have been inconsistent.

In the study by Meshkat and Nejati (2017), the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory was administered to 455 undergraduate university students. Results showed no significant difference between males and females on the total score measuring EI.

However, female students scored higher than males on self-awareness, interpersonal relationship, self-regard, and empathy. Although, given previous research, Meshkat and Nejati (2017) expected males to score higher than females on self-regard, in actual fact the findings of this study did not support this hypothesis.

What about other research?

In a US study, females scored higher on EI than males on EI and had higher emotional and interpersonal skills, whereas, in India, a study of medical graduates found the females to be higher in EI.

A study of Sri Lankan undergraduate medical students also found females to have a higher average level of EI. In younger students, a study in Delhi found that female 10th graders demonstrated higher EI than their male counterparts, however in a study that took place in Iran, 17-year-old female students had a lower EI.

Overall, it has been suggested that females tend to score higher EI than males. However, even this finding is inconsistent!

In some cases, there are no clear differences – for example, a study in the UK failed to find any relationship between gender and overall EI in a sample of employees. Similarly, in a study based in Myanmar, no difference in EI was found between male and female teachers.

Perhaps, then, we should examine the components of EI. Indeed, females ranked more highly than males in terms of the interpersonal facet of EI, as well as in empathy, emotional skills, and emotional-related perceptions (such as decoding facial expressions).

There are also gender differences in the expression of emotions – females tend to be better at expressing emotions.

It has been found that mothers use more emotion words when telling stories to their daughters, and also display more emotion when interacting with females. It has also been claimed that males actually fear emotions and struggle to name the emotions experienced by themselves or others.

Research has shown that males are more likely to express high-intensity positive emotions, such as excitement, whilst females tend to express low/moderately intense positive emotions (such as happiness) and sadness.

Further, research suggests that females pay more attention to emotions, are more emotional and tend to be better at handling emotions and understanding them. On the other hand, males have been shown to be more skillful at regulating impulses and coping with pressure.

Females tend to be more able to guide and manage the emotions of themselves and others, and they also tend to be better at emotional attention and empathy than males, who show superiority in emotion regulation.

In the workplace, more specifically in the area of leadership, males tend to be more assertive, whilst females demonstrate higher levels of integrity than their male leader counterparts.

One consistent finding into gender difference in EI was that in nearly all countries, males were found to overestimate their EI whilst females tend to underestimate their EI.

As you can see, the question of whether there are gender differences in emotional intelligence is not easily answered. Overall, however, there does seem to be an association between gender and EI.

Role of EQ in Self-awareness

Self-awareness can be defined as the ‘conscious knowledge of one’s own character and feelings’. In his best-selling book “Emotional Intelligence” published in 1995, Daniel Goleman defines self-awareness as ‘knowing one’s internal states, preference, resources, and intuitions’.

What, then, is the role of EQ in self-awareness?

Well, considering that the first step in awareness is ‘knowing’, EQ enables an individual to notice different emotional reactions – therefore giving them the knowledge of what is being experienced themselves or by another person.

The next step is another component of EQ: being able to identify the emotions correctly (Cherry, 2018). Another feature of being self-aware is the capacity to realize how our actions, moods, and emotions affect others – which is also a component of EQ (Cherry, 2018).

Monitoring one’s emotional experience is another skill of EQ related to self-awareness.

Another factor in being self-aware is being able to notice the relationship between our feelings and our behavior, as well as being able to recognize our own strengths and limitations (Cherry, 2018).

While self-awareness necessarily affects the individual, according to Goleman, the self-awareness component of EQ also includes having an open mind when it comes to unfamiliar experiences and new ideas, and also to take lessons from day-to-day interactions with others.

As you can see, self-awareness is a key component of EQ, and the two are interdependent.

The Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence

The following section of the article is based on the information freely available at www.ei.yale.edu.

The Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence was founded by Peter Salovey, and is currently being directed by Marc Brackett. The Center “uses the power of emotions to create a more effective and compassionate society”.

A key aspect of the center is the application of scientific research to develop effective approaches for teaching EI. It also seeks to provide education on how to develop EI across the lifespan.

In a range of schools, the Yale Center uses a research-based, field-tested approach called RULER.

RULER was inspired by Marvin Maurer, a teacher who, in the early 1970s began using an emotional literacy program. RULER has been associated with improvements in students’ academic performance and social skills.

It has also been shown to help develop classrooms that are more supportive and student-centered. It includes tools, such as the ‘mood meter’: a RULER tool that helps students recognize and communicate their feelings.

Classrooms using RULER report less aggression among students than those classrooms not using RULER.

To learn more about RULER, a research article has been listed as one of the recommended papers in the earlier section of this article.

The Yale Center for EI’s mission is to utilize research to enhance real-world practice. The success of RULER has led Yale to produce similar programs to be delivered in ‘communities’ such as businesses, governments, and families.

The overarching aim is to harness the power of EI to help individuals achieve happier, healthier, and more productive lives.

Partners of the Center include the Born This Way Foundation, the Brewster Academy, and CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning). The Yale Center is currently being supported by Facebook in researching the nature and consequences of online bullying among adolescent Facebook users.

The Center aims to study new ways to teach EI.

Researchers have published over 400 scholarly articles, a number of curricula for teaching EI and several books on the topic of EI. It looks into how EI skills are taught and assessed in people of all ages. Further, it has investigated how best to assess EI in a variety of contexts and the development of EI skills throughout life.

Researchers at the Yale Center for EI are also looking into the roles emotions play in everyday contexts, including work and school. One example is the ‘Creativity, Emotions and The Arts’ project.

The Center is also researching bullying, with the aim of creating positive, safe emotional environments where bullying behaviors do not flourish.

Emotional Intelligence and the Brain: Advancements in Neuroscience

In the past, cognitive and emotional processes were understood to be different constructs. A study by Barbey and colleagues in 2014 provides neuropsychological data to suggest that emotional and psychometric (i.e. general) intelligence are both driven by the same neural systems – therefore integrating cognitive, social, and affective processes.

The study led by Aron Barbey (University of Illinois neuroscience professor) showed that general intelligence and EI share similarities both in behavior and the brain – many of the brain regions were important to both general and emotional intelligence (Yates, 2013).

Barbey’s study looked at the neural basis of EI in a sample of 152 individuals with focal brain injuries (Barbey et al., 2014).

Researchers looked at task performance on a range of tests designed to measure:

- EI (using the Mayer, Salovey and Caruso EI test – MSCEIT)

- General intelligence (using the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition – WAIS-III)

- Personality (using the NEO-PIR)

The researchers studied these phenomena by using CT scans and developing a 3D ‘map’ of the cerebral cortex, which they then divided into 3D units called ‘voxels’ (Yates, 2013).

They then compared the cognitive abilities of those with damage to a particular voxel, or cluster of voxels, with those who had no such injuries in the brain region (Yates, 2013). Then they looked at the brain regions utilized to execute specific cognitive abilities, those associated with general intelligence, EI, or both.

Barbey et al. (2014) found that impairments in EI related to specific damage to the ‘social cognitive network’. This network is made up of the extrastriate body area within the left posterior temporal cortex, which is associated with perception of the form of other human bodies, and the left posterior superior temporal sulcus, which plays a role in interpreting movement of the human body in terms of goals (Barbey et al., 2014).

The social cognitive network also comprises of the left temporoparietal junction, which supports the ability to reason about what makes up mental states, and the left orbitofrontal cortex, which is recognised as supporting emotional empathy and the relations between two minds and an object – thus supporting shared attention and collaborative goals (Barbey et al., 2014).

Although the study showed that the neural networks of EI were distributed, the neural substrates of EI were concentrated in the white matter (Barbey et al., 2014).

There was found to be a significant effect on EI with lesions in white matter sectors such as the superior longitudinal/arcuate fasciculus that connect the frontal and parietal cortices. EI substrates were also found within a narrow subset of regions associated with social information processing.

Overall, the findings of Barbey et al. (2014) provide evidence that EI is supported by the neural mechanisms that regulate and control social behavior, and that the communication between these brain areas is critically important.

The orbitofrontal cortex is a key part of the neural network for regulating and controlling social behavior (Barbey et al., 2014). It has been suggested that the orbitofrontal cortex plays an important role in emotional and social processing – studies have also supported the role of the medial orbitofrontal cortex in EI.

The neural system for EI also shared anatomical substrates with specific facets of ‘psychometric’ intelligence (Barbey et al., 2014).

According to Barbey (as reported in Yates, 2013):

“Intelligence, to a large extent, does depend on basic cognitive abilities, like attention and perception and memory and language. But it also depends on interacting with other people. We’re fundamentally social beings and our understanding not only involves basic cognitive abilities but also involves productively applying those abilities to social situations so that we can navigate the social world and understand others”.

This neuroscience study provides an interesting perspective on the interdependence of general and emotional intelligence.

A Take-Home Message

Hopefully, by reading this article, you are now aware of the important part emotional intelligence plays in each of our lives. EI provides life with flavor! By understanding the feelings of ourselves and others, and allowing this knowledge to enable us to reason and make decisions, we enjoy what is the unique experience of being a human being.

I will readily admit that I have learned a lot about EI writing this article, and I am hoping that you have learned something new too. Perhaps you are now interested in spending some time reading one of the research papers that were recommended earlier in the article, or for something a little lighter, why not check out our 15 Most Valuable Emotional Intelligence TED Talks.

I welcome your input on this diverse area of positive psychology – how are you aware of EI in your day-to-day life? In your experience, do you think that EI can be linked to personality traits? What would a world without EI look like?

Thanks for reading this article!

For further reading:

- 13 Emotional Intelligence Activities & Exercises

- How To Improve Emotional Intelligence Through Training

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free.

- Barbey, A. K., Colom, R., & Grafman, J. (2014). Distributed neural system for emotional intelligence revealed by lesion mapping. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9(3), 265-272.

- Cherry, K. (2018). 5 Components of emotional intelligence. Very Well Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/components-of-emotional-intelligence-2795438

- Denham, S. A., Blair, K. A., DeMulder, E., Levitas, J., Sawyer, K., Auerbach–Major, S., & Queenan, P. (2003). Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development, 74(1), 238-256.

- Faltas, I. (2017). Three models of emotional intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314213508_Three_Models_of_Emotional_Intelligence/download

- Mayer, J. D. (2009). What emotional intelligence is and is not. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-personality-analyst/200909/what-emotional-intelligence-is-and-is-not

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review, 8(4), 290-300.

- Mayer, J. D., Roberts, R. D., & Barsade, S. G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 507-536.

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2004). Emotional intelligence: Theory, findings and implications. Psychological Inquiry, 15(3), 197-215.

- Meshkat, M., & Nejati, R. (2017). Does emotional intelligence depend on gender? A study on undergraduate English majors of three Iranian universities. SAGE Open, 7(3), 1-8.

- Resilient Educator. (2020, June 11). Daniel Goleman’s emotional intelligence theory explained. Retrieved from https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/daniel-golemans-emotional-intelligence-theory-explained/

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.

- Yates, D. (2013). Researchers map emotional intelligence in the brain. Illinois News Bureau. Retrieved from https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/271097

Let us know your thoughts

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (18)

- Positive Parenting (4)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

What our readers think

Hello,

Really the article was so educative. Reading it added many things to my knowledge.

Thank you.

Hi Nicole, I found the article extremely useful as a professional in the finance industry, especially, the potential gender differences in EI. From observations of my peers and comments from others, empathy in my profession is very important to relating to clients and therefore providing appropriate advice. I am utilising the knowledge gained in EI to improving outcomes for my clients.